Layman Paper Summary: Humans treat unreliable filled-in percepts as more real than veridical ones

We recently published an article (free to read): “Humans treat unreliable filled-in percepts as more real than veridical ones”. Inspired by Selim Onat and many others, I try to to explain the main findings in plain language. First let me give you some background:

To make sense of the world around us, we must combine information from multiple sources while taking into account how reliable they are. When crossing the street, for example, we usually rely more on input from our eyes than our ears. However we can reassess our reliability estimate: on a foggy day with poor visibility, we might prioritize listening for traffic instead.

The human blind spots

But how do we assess the reliability of information generated within the brain itself? We are able to see because the brain constructs an image based on the patterns of activity of light-sensitive proteins in a part of the eye called the retina. However, there is a point on the retina where the presence of the optic nerve leaves no space for light-sensitive receptors. This means there is a corresponding point in our visual field where the brain receives no visual input from the outside world. To prevent us from perceiving this gap, known as the visual blind spot, the brain fills in the blank space based on the contents of the surrounding areas. While this is usually accurate enough, it means that our perception in the blind spot is objectively unreliable.

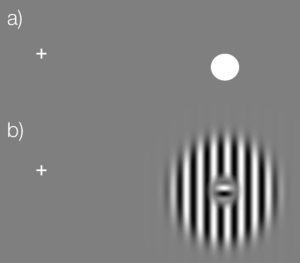

You can try it out by using this simple test (click the image to enlarge)

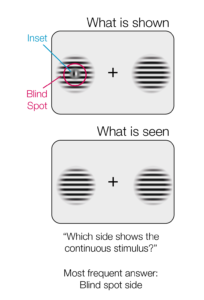

Keep your eyes fixed on the cross in (a). Close the left eye. Depending on the size & resolution of your screen, move your head slowly closer to (or sometimes further away from) the screen while looking at the cross. The dot in (a) should vanish. You can then try the same with the stimulus we used in this study (b). The small inset should vanish and you should perceive a continuous stimulus.

What we wanted to find out

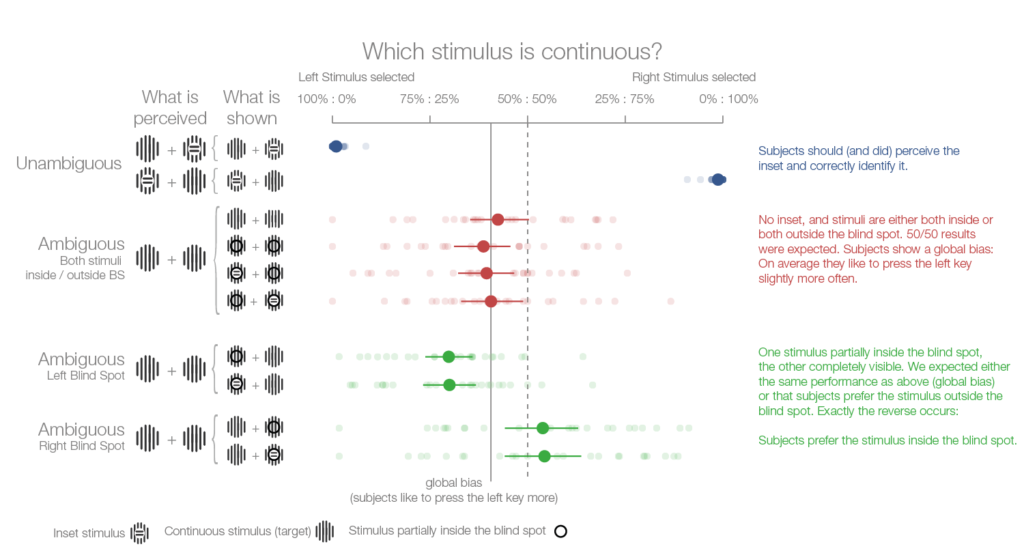

To find out whether we are aware of the unreliable nature of stimuli in the blind spot we presented volunteers with two striped stimuli, one on each side of the screen. The center of some of the stimuli were covered by a patch that broke up the stripes. The volunteers’ task was to select the stimulus with uninterrupted stripes. The key to the experiment is that if the central patch appears in the blind spot, the brain will fill in the stripes so that they appear to be continuous. This means that the volunteers will have to choose between two stimuli that both appear to have continuous stripes.

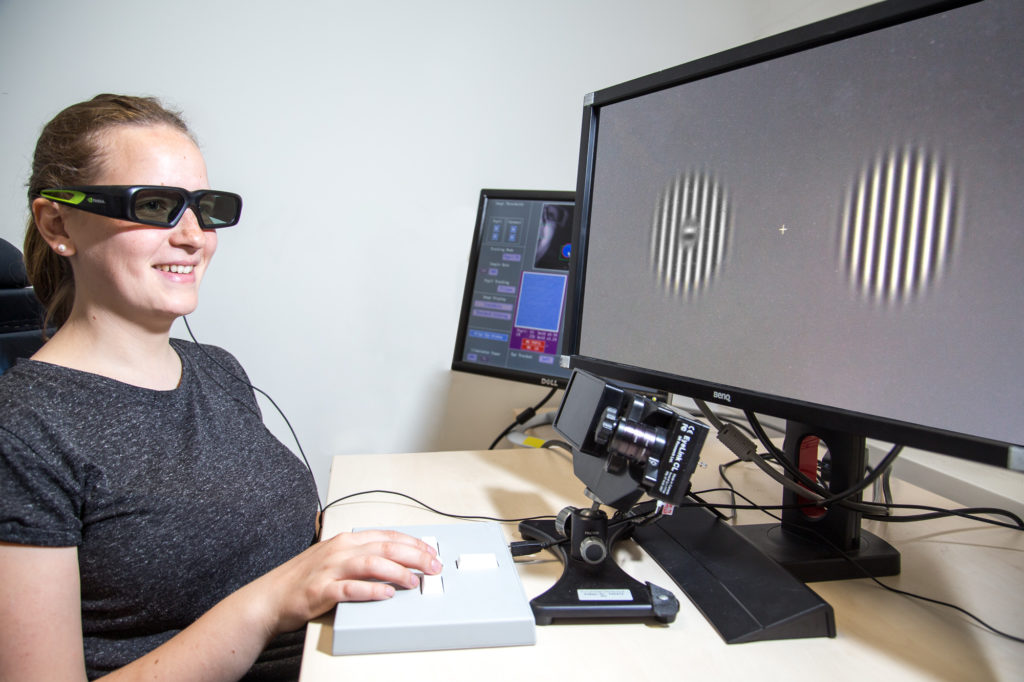

A study participant chooses between two striped visual images, one ‘real’ and one inset in the blind spot, displayed using shutter glasses (CC-BY 4.0 Ricardo Gameiro)

What we thought we would find

If subjects have no awareness of their blind spot, we might expect them to simply guess. Alternatively, if they are subconsciously aware that the stimulus in the blind spot is unreliable, they should choose the other one.

In reality, exactly the opposite happened:

The volunteers chose the blind spot stimulus more often than not. This suggests that information generated by the brain itself is sometimes treated as more reliable than sensory information from the outside world. Future experiments should examine whether the tendency to favor information generated within the brain over external sensory inputs is unique to the visual blind spot, or whether it also occurs elsewhere.

Sources

All images are released under CC-BY 4.0.

Cite as: Ehinger et al. “Humans treat unreliable filled-in percepts as more real than veridical ones”, eLife, doi: 10.7554/eLife.21761